The Stone Whisperers of Agra: Unpacking the Art, History, and Secrets of Marble Inlay (Pachchikari)

Hello, history lovers and treasure hunters! If you’ve ever gazed at the sheer brilliance of the Taj Mahal, you’ve witnessed one of the world’s most exquisite examples of marble inlay work. This isn’t just decoration; it’s a centuries-old craft rooted in India’s glorious Mughal past. Ready to dive into the sparkling secrets hidden within Agra’s famous white stone? Let’s explore the art, the artisans, and the magic of Pachchikari.

I. Introduction: The Gemstones that Built a Wonder

Globally, you might know this technique as Pietra Dura. This is the Italian term meaning ‘hard stone,’ and it describes the craft of embedding fine pieces of coloured stones to create striking decorative images. But when you’re strolling through India, you’ll hear the native Mughal term: Parchinkari or Pachchikari, which literally translates to ‘inlay’ or ‘driven-in’ work.

This dazzling craft is fully alive and thriving right in the streets of Agra, the city of the Taj Mahal in Uttar Pradesh. And the reason Agra is the epicentre? The most famous, the “most sumptuous expression,” and the “most splendid expression” of this art is, of course, the Taj Mahal itself.

II. History and Grandeur: The Royal Patrons of Pachchikari

The history of marble inlay involves a fascinating blend of cultures and artistry.

A. Defining the Dual Identity

The origin of the craft is often debated. The Italian art appeared in Rome in the 16th century and reached Florence, attaining a classical form. By the 17th century, smaller objects showcasing this technique began reaching the Mughals in India, often arriving as presents. Though some believe the art is Italian in origin, the accomplished Indian artisans were quick to adapt the technique, giving it an “indigenous touch” and reinterpreting it into the distinct ‘Mughal style’.

B. The Age of Marble (Shah Jahan)

The craft developed slowly during the 16th and 17th centuries under the reigns of Akbar and Jahangir. However, it truly came into its own under Shah Jahan. The Tomb of Itmad-ud-Daulah provides a crucial link here; it represents the transition from the red sandstone architecture (Akbar’s buildings) to the use of white marble with rich ornamentation in pietra-dura favoured by Shah Jahan. Other architectural examples of remarkable inlay work include the marble pillars in the Diwan-e-Aam and the Musamman Burj in the Agra Fort.

C. Myth and Symbolism

For the Mughals, these designs were more than just pretty flowers. They often represented deep cultural and religious beliefs.

- Geometric Patterns: Geometric patterns are commonly used in Pachikari and are assumed to express the abstract and infinite nature of Allah. The use of circles, squares, stars, and multisided polygons helps illustrate spiritual concepts without violating the tradition of avoiding figural representations.

- The Solomonic Catalyst: Did you know that some sources suggest the catalyst for this craft was the myth of the Solomonic throne? Imagery symbolizing King Solomon’s great power, wisdom, and justice was inlaid in the niche behind Shah Jahan’s jharokha in Delhi.

III. The Art of Inlaying: Process, Materials, and Motifs

The sheer complexity of Pachchikari is what makes it so valuable. Every piece you see is the result of intricate, time-consuming labour.

A. Core Materials

The foundation for this magnificent work is Makrana marble.This premium marble, brought from Makrana in Rajasthan, was famously used for the Taj Mahal and is chosen because its quality allows for very fine and intricate work.

The colours, however, come from semi-precious stones. Some common stones you’ll find include:

- Lapis Lazuli (Dark Blue)

- Cornelian (Orange)

- Malachite (Dark Green)

- Turquoise (Milky Blue)

- Jasper (Brown) The cut stones are secured using a masala mixture of gum, marble dust, and araldite.

B. The Detailed Process

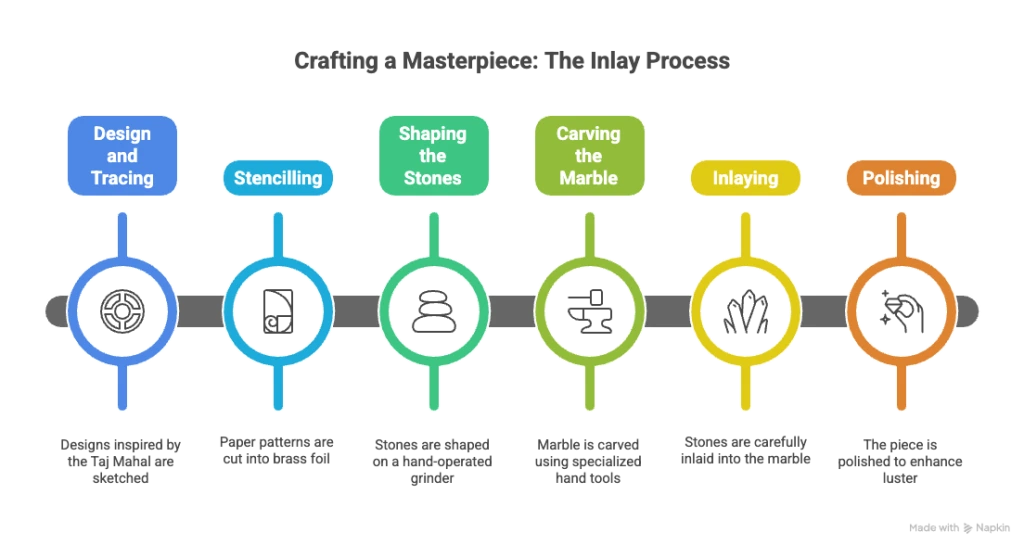

This craft relies on the remarkably trained hands of the karigars, or skilled labourers:

- Design and Tracing: Designs, often inspired by the Taj Mahal’s floral and geometric patterns, are sketched onto tracing sheets.

- Stencilling: The paper patterns are stuck onto brass foil and cut, forming stencils.

- Shaping the Stones: The design is traced onto the semi-precious stones. The stones are then shaped precisely on a hand-operated grinder. Smaller stone pieces can even be joined together using lac before shaping.

- Carving the Marble: The design is etched onto the marble piece, and the marble is carved out accordingly. This carving uses specialized hand tools like Tankiya and Narzia.

- Inlaying: The intricate shaped stones are carefully inlaid into the grooves, secured with the masala.

- Finishing: The piece is polished on grinders attached with buffs to enhance the luster and reveal the masterpiece’s beauty.

IV. Contemporary Practice and Practical Advice

While Pachchikari’s origins lie in monumental architecture, today its purpose has shifted to accommodate the global market, allowing us to bring a piece of that history home.

A. Treasure Hunting in Agra

The high tourist demand in Agra is a significant driving force that keeps this craft alive.

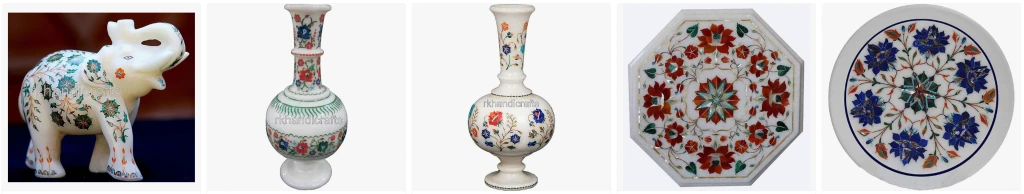

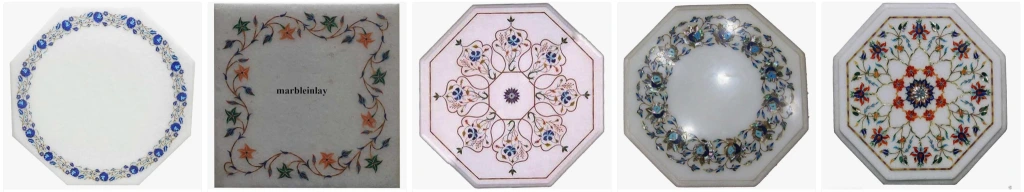

- What to Buy: The craft’s use on large constructions is now mostly a tradition of the past. Instead, you can find a flourishing industry of artifacts ranging from table tops (including dining, coffee, and side tables), jewellery boxes, trays and plates, vases, and intricate chessboards.

- Where to Shop: You can find these items in artisan-heavy areas of Agra, like Gokulpura or Nai Ki Mandi. Specific boutiques, such as Kalakriti, specialise in these objects and carry the work of more than fifty families. If you can’t make it to Agra, many factories now sell their beautiful, unrivalled objects “on internet worldwide”.

B. Expert Tips: How to Spot Quality

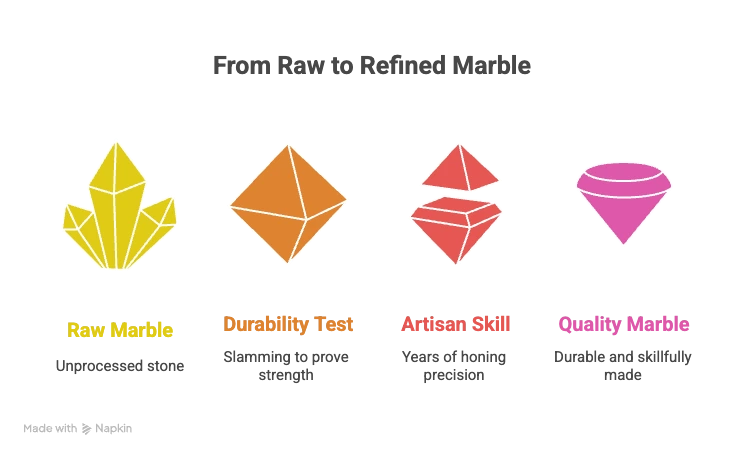

If you are planning to purchase a piece, here’s what the experts want you to know:

- The Durability Test: The local guide in Agra might demonstrate the quality by slamming a decorated tabletop back onto its legs! This is to show you that “Indian marble is not fragile, like Western marble”. They may even pour soda across the table to prove that the material is built to last.

- Generational Skill: The precision of fitting the stones is “purely determined by the artisan’s experience“. Since it can take five to ten years to become adept at just a single step in the process, the longevity of the artisan’s skill is a key indicator of quality.

C. The Artisan Challenge

Despite the beauty and global fame, the craft faces modern challenges. The skill is often passed down through generations of close family members. However, the process is highly labour intensive and time consuming. Artisans often lament that the craft is not providing “enough livelihoods”. With young people increasingly choosing “white-collar careers” and universities, there is a risk that this deeply rooted generational skill may struggle for new talent.

V. Agra Travel and Local Culture (Bonus Insights)

If this has inspired you to visit Agra, here are some friendly tips to enhance your trip:

- Getting There: Agra is situated on three major National Highways and is well-connected by rail. You can reach Agra from Delhi via the Yamuna Expressway in about two hours.

- Best Time to Visit: The best time to visit is August–November.

- Local Co-operation: Keep an eye out for the local community dynamics. The difficult task of stone inlay finishing and polishing is often shared between Muslim and Hindu craftsmen, showcasing a beautiful spirit of co-operation in the production of this art.

- Must-Eats: You can’t leave Agra without trying its famous sweets! Look for Petha (made from pumpkin), Gajak, Dal moth (a savoury snack), and the renowned breakfast specialty, Bedai Jalebi. You can also catch the Taj Mahotsav, a ten-day festival of crafts and arts held in February.